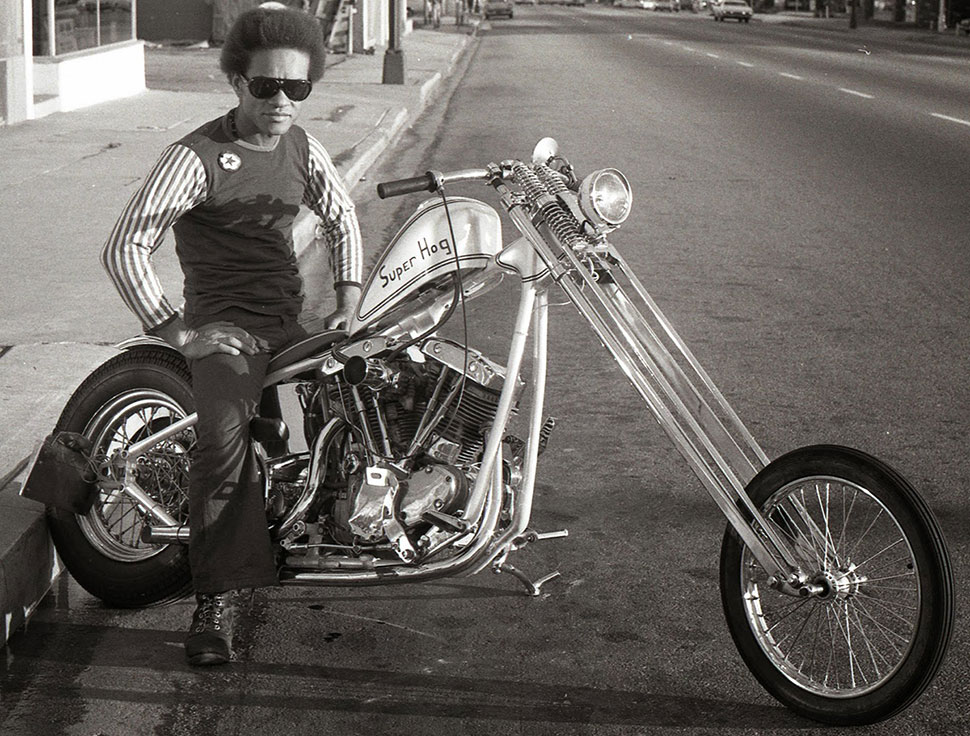

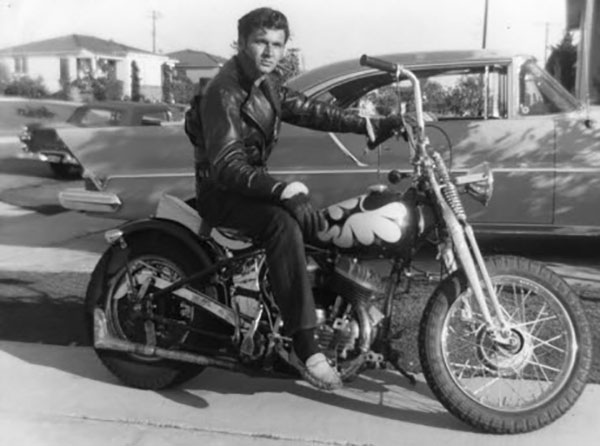

Consider the classic Harley chopper, a motorcycle which has been modified heavily from stock, primarily to remove bulky fenders and trim in favor of light, slimmer options, to change the steering angle and frame geometry, with wheel, fork, and gas tank choices made in such a way as to lengthen and narrow the bike, creating a longer bike that, yes, didn’t handle as well as the original, and often was considerably less comfortable and didn’t necessarily stop as well. But they looked wonderful as objects d’art, if not examples of superior craftsmanship and creativity. They were the “thing” in the 60s and 70s, and the more radical the better, until they kind of disappeared from the scene by the end of the 80s except in Sweden, of all places, where they took the ball and ran with it, creating the “Swedish style.” But we loved ‘em, just the same, and a new generation of bikers and builders have discovered the chopper as a form of creative expression with a vengeance.

Competition Led to the Harley Chopper

The chopper didn’t spring into existence from nothing, however, it evolved from the bikes of the 40s and 50s that were the first “bobbers,” a term that is horribly misunderstood today. Performance modifications in the late 40s and 50s often meant grinding your own cam profiles or adapting side draft carburetors from small import cars (American cars used down draft carbs, and the Harley and Indian side draft, so side draft carbs from British cars – the SU, and German cars – the Weber, became performance options for American bike builders). Performance parts just weren’t widely available to Harley owners at the time. Imported British TT bikes were quicker and lighter than the Harleys and Indians on the road, both Flathead and overhead valve models, and by the 1950s, the Triumph twins were hard to beat in a street race. Harley introduced the K-Model in 1952 to compete in TT races and on the flat track, and in 1957 added an overhead valve top end, and the Sportster was born. But there was a decade or two’s production of Harley overhead valve and Flathead Big Twins on the road (1936 was when the OVH Knucklehead 61” EL was introduced, as well as the 74” and 80” Flathead U series bikes) and there were also many many surplus Flathead 45” WLAs war bikes to be had for as little as $50, and lots of folks just didn’t take to the imports. Instead, they looked to the American bikes they knew and loved and sought ways to improve their performance.

By the 1950s, the British twins from Vincent, Ariel, Triumph, BSA and others were simply the fastest bikes on the road in any numbers. This was, of course, unacceptable to those folks who loved their Harleys and Indians to the exclusion of any other brands, and the easiest solution for improved performance was to remove weight from the bike. Removing 45lbs from a 450lb – dropping 10% of the weight of the bike – would effectively give you a 10% increase in usable power, and when the most powerful stock Harley Big Twins were sporting just under 50 horsepower, 10% was a substantial increase.

The Origin of the Bobber Motorcycle

So, just as when a gal getting her hair cut short was called “a bobbed haircut” or “a bob,” bikes that had been stripped of as much weight as they could were the original “bobbers.” Yup, that’s where the term comes from, and a bobber was a bike that had all the extraneous trim and sheet metal removed, producing a look that became more common as the 1950s progressed. Riders would remove the heavy 16” front wheels and put lighter, thinner 18” and 19” front wheels on their bikes, often taken from British bikes. They’d remove the heavy front fender from glide or springer front ends completely, or replace it with a lighter, narrower fender from the same bikes the wheels came from. They’d remove the big heavy muffler and save another 5-10lbs and improve performance a bit. They’d remove the hinged tail off the rear fender, or replace completely with a flat fender made for lightweight trailers, available from the JC Whitney catalog or a local hardware store. Remove the cowling from wide glide forks, swap in a smaller Bates headlight, and remove the big tractor seat and seat tube and spring in favor of small Bates solo saddles and pillion pads from those same British bikes, add an SU carburetor or an additional Linkert carb to a custom made intake manifold, and your Flathead, Knucklehead or Panhead, or Indian Scout or Chief could perform as well as the British twins.

As the 50s progressed, people with the customization bug took hold. Car customs were becoming a big thing, too, and hot-rodders and drag racers were making wild changes to stock cars. Motorcycles weren’t far behind. Riders began looking for style changes, and the Hummer and Sportster “peanut” gas tanks, while providing a smaller fuel capacity, were considerably lighter than the split tanks, dashboard, and speedometer of the stock bikes, and bikes were otherwise stripped to about as far as they could go. Style changes came from unusual places- fishtail and megaphone exhaust from British bikes became inexpensive style modifications to American bikes. Springer, girder and glide forks were extended by creative welders to increase ground clearance a bit, then a bit more, then a lot. Modify the frame neck to accommodate the longer forks without picking the bike up too far, and the chopper was born.

The Evolution and Spread of Chopper Culture

Chopper culture, as well as custom car culture with builders like George Barris and Ed Roth, was at its height in the 60s and 1970s, but by the early 1980s, most of the long choppers were remodded back to more practical configurations, or sat in the corner collecting dust while disc brake bikes with electric starters became more prevalent and Japanese imports took over the largest section of the motorcycle market. As choppers got wrecked or repurposed, folks without much budget would begin shifting back to glide forks which were readily available in parts collections. As preferences in style and taste changed, and the availability of more effective disc brakes and swingarm frames lent themselves to more comfort and practicality to an aging biker population, the chopper in the US became a fetish that held interest for few builders. The riders in their twenties and thirties in the 50s and 60s were now in their forties and fifties and even sixties, and wanted something more comfortable and practical. And yeah, a lot of bikers wanted a bike that could stop better, too.

In Sweden and Europe however, chopper culture got started a bit late. The Swedish chopper looked a lot like the American chopper, but with extremely long forks, and rode low to the ground. The Swedes, not having a large supply of surplus US Army flatheads to pirate springer forks from, resorted in most cases to using very long fork tubes on hydraulic forks, modifying frame necks for severe rake, and created a style of their own that still survives today. In the 1990s and 2000s, the Swedish chopper style was taken on by American boutique builders creating “Pro Street” bikes, with long fork tubes, rigid and softail frames, and the “long and low” look of the Swedish chopper returned to the US as wealthier buyers spent tens of thousands of dollars on customs from builders who did nothing but build wild pro-street choppers. But the chopper of old had not died completely, and bike and parts were in garages all over the US and even Canada.

By the end of the 80s, the advent of the Evo motor, the rubber mounted engine and tranny of the FXR, and Harley’s “factory customs” like the Sturgis, the Wide Glide, and the Low Rider, bikes that looked more like the bobbers of the 1950s but with larger fuel capacity had become the order of the day. When Harley introduced the first Softail models, which were a compromise between the looks of the classic rigid frames of the Pan and Knuckle, while having *some* rear suspension, the chopper was effectively an anachronism to be seen mostly at bike runs or covered in dust in the back of the garage. Lots of bikes were returned to their original form, as restorers began snapping up vintage barn finds and garage queens in large numbers and by the early 2000s, vintage restored bikes were bringing high dollar at auctions across the US.

The Modern Rebirth of Choppers

Sometime after the year 2000, however, the vintage chopper began to make a comeback, and in the last 5 years they’ve taken on a life like most folks wouldn’t believe. Whether it’s the resurrection of Dad’s old chopper collecting dust in the garage, or assembled from swap meet parts, to building with new parts and a “donor” bike, chopper culture and choppers are seeing a resurgence in popularity that in my estimation surpasses the popularity at their heyday. The internet is probably as responsible as anything for this, as eBay made parts more available, and in the last few years web apps like Instagram became a place where bike parts and engines and even whole bikes were traded and sold. Groups like Chopcult and the various Harley forums, and online parts and customization vendors have helped lead a chopper building genesis that is both refreshing and new. Modern machine tools, fabrication techniques, and welding shops are turning out narrowed triple trees, custom handlebar configurations, and frame mods in ways that were never practical in earlier times. And just as restored vintage bikes, performance FXRs and Dynas, and custom big-inch baggers are seeing huge interest, tons of money spent, and some amazing examples of innovation, the “long” chopper of the 60s and 70s are again spreading over the planet, anywhere people have motorcycles and the internet.

In recent years there has been an enormous growth in interest and building of old school Harley choppers (other brands, too, but not so much as Harley and, well, I’m a Harley guy). A quick look at Instagram with chopper-centric hashtags, or a Google image search will show you many old-school choppers with stretched springer or girder front ends, lengthened and narrowed tube forks, and frames built or modded in rake and stretch to accommodate such things. Rigid frames are coming back with a vengeance, and the old chopper forks that have collected rust in garages around the country are coming into the light of day, being rebuilt and refurbished with new bushings, and sold and traded online and in swap meets like they’re going out of style. The “patina” of age, rust, and generally well-used parts is now a desirable style, believe it or not, and a rusty springer front end from the 60s is going to be snapped up much more quickly than a pristine reproduction piece, and it’s just as likely to be bolted onto a bike as is, rust and all.

Chopped Panheads, Shovelheads, Evo Big Twins, and even Sportsters are being built, rebuilt, and ridden as daily rider bikes, maybe in greater numbers than they were in the 60s and 70s.

Harley Sportster – The Everyman’s Chopper

Unsurprisingly, the venerable Sportster has become the “gateway” bike for chopper builders and riders, since donor bikes are inexpensive now, just as they were in the 60s and 70s, when they were the bike folks on a severe budget bought and built for their first chopper. Chopped Sportsters are seeing a comeback and popularity in a way they never did even in the 60s when the Ironhead 900cc Sportster was pretty much the hottest thing on two wheels until the Honda 750 came along and imports took over the market in the 70s and early 80s. Chopper culture has looked to the Sportster, Ironhead and Evo alike, as an inexpensive way to build a bike that looks like the bikes of yesteryear, and with the prevalence of electric start Evo Sportsters for so little money, chopper builders can avoid the anecdotal “kicking til you’re blue in the face” stories that older folks will relate of days gone by. Yes, we were building Ironhead choppers in the 60s, 70s, and early 80s, but not nearly in the numbers you see today. Cheap Evo Sportsters can be had in pristine, low-miles stock running condition for as little as $1000-1500 for a 1980s and early 90s model to $3000-3500 for a Sportster from 10 years ago. Buy a new chopper rigid frame from any number of vendors, or weld on a hardtail, stretch and rake the frame neck, add a vintage or new aftermarket springer front end or narrow trees and long fork tubes for the original hydraulic front end, and VOILA! You have a 1960s style chopper that is unlikely to have most of the reliability issues that Sportsters were known for in the past, and for less than the cost of a 10 year old Dyna Street Bob in most cases. Of course, the mechanic building and maintaining the bikes today, just like in the old days, will be the biggest difference between a reliable ride and needing to own a pickup truck.

The chopper today has developed a growing and devoted following, and creative builders are putting together bikes that bikers in the 60s would be envious of. Take a look at chopper hashtags on Instagram, and do those Google image searches and you’ll see more modern “vintage” choppers than you knew existed. Many folks are making stylistic choices that were a matter of practicality for those in the past, but that’s part of the allure of the vintage chopper. They don’t handle as well as a modern bike, and they often don’t stop as well, either, but the chopper is back with a vengeance and they’re not going away any time soon.

A great informative article(as always).. Ride On

Thanks Rod. Ride safe.

I built the black rigid chopper with the leather tank strap. The strap is actually a tooled leather guitar strap.

When I lived in the Haight, the “angels” used to hang out at one place on Haight St.

There was one chopper which was purple with a molded tank.

It was one of the really great looking bikes and the time and, it was called the “Time Machine”.

This was in the late 60’s.

I don’t care about the guy who owned it butt, it was a great looking chopper.